My next review is of Inferior:How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story by Angela Saini. The theme of this book is encapsulated in the subtitle. The chapters of the book cover eight broad topics around how science has treated women. Typically they outline something of the background of the established view, and then go on to discuss some more recent revisions.

My next review is of Inferior:How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story by Angela Saini. The theme of this book is encapsulated in the subtitle. The chapters of the book cover eight broad topics around how science has treated women. Typically they outline something of the background of the established view, and then go on to discuss some more recent revisions.

It all starts with Darwin and a letter from an American suffragette, who receives a somewhat dusty response from him regarding what he sees as the proper,evolved and, undoubtedly lower status, state of women. But Darwinism does give women an opportunity: no longer is their position ordained by God but it is now subject to environment and the laws of nature so a new space for interpretation and equal rights opens up.

The next chapter covers health and longevity, it fits to a degree with the final chapter on the menopause. Women typically live a bit longer than men though are slightly more prone to illness, particularly autoimmune diseases. For various reasons women have tended to be un-represented in medical trials, this is being addressed now. Looking back, the treatment of the menopause as a medical problem to be resolved rather than a normal part of life, is problematic. I think it may have happened to a lesser extent with men with declining libidos in later years being addressed with Viagra. The difference being that Viagra is a short term “solution” whereas HRT has tended to be a long term intervention with unknown side-effects. For many aspects of this book we can look to other animal species to see how they are similar or different to humans, with the menopause pickings are sparse. Pretty much the only example is the orca, where mothers appear to nurture their male offspring throughout there lives.

Much of the recent scientific view on human sexuality are derived from some experiments on fruit flies done in the late 1940s. They showed that males were more promiscuous than females, and the conclusion drawn from this was that males benefitted from spreading their seed more widely whilst females only needed to be fertilised once. This was reinforced by experiments, which can only be described as unethical, involving sending out students to proposition members of the opposite sex. It turns out that men were more likely than women to go sleep with a stranger. But clearly women are considering more than just reproduction in such scenarios – they face a real threat of violence.

Across the world zookeepers are puzzled as to why some of their male bonobos get beaten up by females. All manner of exceptional explanations are provided for this. But fundamentally it is because bonobos have a matriarchal society in which males lacking the protection of females (in particular their mother) are vulnerable to bands of marauding females. This is the reverse of the situation in other primate specifies such as chimpanzees and orang-utans where isolated females are targeted by males.

There is an air of desperation to the efforts to demonstrate that women are different in all manner of biological ways, rather than accept that actually it is the way that society treats women that leads to their disadvantage. Or even consider it, for that matter. Intelligence, or scientific achievement, is covered in a couple of chapters, one of which is entitled “The missing five ounces of the female brain”. Fundamentally the problem here is trying to pull apart abilities such as spatial reasoning on an axis (gender) that fundamentally isn’t that important. It turns out across a wide range of human abilities it’s only the ability to throw and the ability to jump vertically where men exceed women by more than a standard deviation. Human abilities can be variable and typically the differences between genders are much smaller than the differences within one gender.

To exclude women from scientific societies, universities and degree courses until the mid-twentieth century and blame their lag of progress in scientific circles as down to some deficiency in their abilities certainly takes some chutzpah. And the fact that we’re doing this in the early years of the 21st century is an embarrassment. Like many women of her time, my mum left her scientific work when she was pregnant with me, and in at least one case was not even given an application form for an administrative post because she was a mother.

Anthropology makes an appearance with a conference entitled “Man the Hunter” from the 1970s. Here man (the male) is seen as the key player going out on the hunt to provide for the tribe. In fact, “gathering” turns out to be more important because hunting is an unpredictable business and only rarely results in the hunter bringing home the dead antelope.

Inferior is written in a style which I found reminiscent of Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes. We are given the context and something of the character of the scientists who Saini interviews. This is in contrast to a lot of scientific writing, even in popular books, which tends to erase the people. I think it is particularly important for a book like this because much of the book is about the character of people. It is striking that almost without fail those arguing for a biological necessity to the the position that women find themselves in are male and those arguing for a new viewpoint based on societal contingency are women.

The change in mindset this brought to me is how obvious the importance of the gender of the researcher is in determining what is studied but also the outcome.

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis

Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis

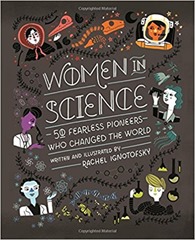

Women in Science

Women in Science