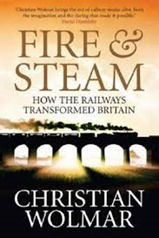

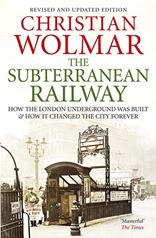

Two interests combine with this book, Railways and The Raj by Christian Wolmar. I picked it up after a recommendation in Empireland by Sathnam Sanghera, which is about the British Empire from an Indian perspective but I’m also interested in railways. I have reviewed Wolmar’s Fire & Steam and The Subterranean Railway in the past. The Indian railway system has been sold as a benefit of colonialism, so I was interested to find out more.

Two interests combine with this book, Railways and The Raj by Christian Wolmar. I picked it up after a recommendation in Empireland by Sathnam Sanghera, which is about the British Empire from an Indian perspective but I’m also interested in railways. I have reviewed Wolmar’s Fire & Steam and The Subterranean Railway in the past. The Indian railway system has been sold as a benefit of colonialism, so I was interested to find out more.

Although the first railways in India were built as early as 1836, not long after those elsewhere, and for similar purposes: for shifting heavy loads short-distances at mines or similar, it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that railway building in earnest started. This followed two reports written by the Governor-General of India, Lord Dalhousie, in 1850 and 1853. In contrast to the chaotic growth of railways in Britain and elsewhere, Dalhousie’s plans, formulated a little after the first rush of railway building, presented a rational and coherent plan for the development of Indian railways.

The start to railway building was slow, with opposition from the East India Company in the first instance, furthermore physical conditions in India were challenging particularly the monsoon season which played havoc with railway bridges over rivers, and whose embankments disturbed the irrigation and drainage in surrounding areas. There were also serious mountain ranges to address.

The Indian railways were built very much for the benefit of the British, most of the rail companies were run from Britain, the levels of return on investment (made from Britain) were guaranteed by the Indian tax payer, most of the equipment (including rails and often sleepers) was sourced from Britain and the economic benefits of the freight transported by the railways were largely in Britain. Not only this, under the Raj, the senior positions in managing and running the railways were held by British people or Eurasians, and this extended to the train staff with drivers predominately British or Eurasian. The British travelling on the railways did so in luxurious first and second class carriages whereas the great majority of Indians travelled in a fairly grim third class.

Class, religious and gender differences were built into the fabric of the railway with various facilities provided separately for Muslim and Hindu passengers, and various castes. I struggle to decide how much this was a deliberate "divide and rule" policy of the British (which was later to have terrible consequences during Partition) or whether it was the right thing to do to respect local sensibilities (although it is fair to say "respecting local sensibilities" was not greatly in evidence during Britain’s colonial period).

There was some development of railways for famine relief – a recurring issue in Indian where millions died through famine in parts of the country. Beyond about 50 miles oxen, the main alternative for transporting food, consume more food than they can carry. The Victorian view was that the railway would carry food to be sold at the market rate from areas of surplus to those suffering famine, which did not greatly help the many poor unable to afford food.

There were lines built for military purposes, particularly in the north west in the direction of Afghanistan from where it was feared a Russian threat would come. More generally, as the railways developed the Indian Rebellion of 1857 was still fresh in the mind of the British and it was felt the railway could help move troops around to quell future rebellions – many early stations were built like fortresses. The railways were important during the two world wars but suffered in these periods from overuse and under-investment.

In a book with a number of shocks for white British sensibilities, I think I found the part on Partition most shocking most probably because it is not something I had thought about before: I knew India had gained independence after the Second World War and that Pakistan, and Bangladesh were part. I had not absorbed that it meant the displacement of between 10 and 20 million people, and the deaths of up to 2 million. 20 million people is a third the population of the United Kingdom and 2 million people is the population of Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham combined.

After Independence and Partition, the successful running of the railways was seen as an important symbol of the success of Independence. Despite the rather hasty British exit, and the lack of home-grown talent and supply chains the post-Independence Indian Railway was quickly much improved.

One recurring theme of the book is the enormous scale of Indian Railways, it employs currently 1.3 million people – globally ranking alongside various Chinese state bodies, McDonald’s, Walmart and the NHS. In the early days the Indian Railways set up company towns in part to service white British employees but also for Indian employees because the railway works were often in otherwise isolated areas. Even now Indian Railways owns huge amounts of property in which its employees live, and also hospitals and schools. It remains central to transport in Indian where the capacity of the airline routes is limited, and the road network is relatively under-developed.

I enjoyed this book as a story of the development of the railway in India, but also as a sketch of Indian history from the middle of the 19th century. To answer my original question, the railway did benefit India ultimately, after Independence, but under colonial rule it was largely a benefit to Britain.